The Forgettable Years of a Coaching Staff to Remember

This story appears in the Aug. 26–Sept. 2, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Mike Shanahan sits at the head of a banquet table. His disciples, roughly two dozen members of the Church of Outside Zone, fill the seats on either side. They’re turning a social event into a coaching clinic—same as always—and it’s getting a little . . . weird. Salt shakers become wideouts. Empty wine bottles stand in for running backs. Slabs of meat, partially dissected, land in the middle of new plays.

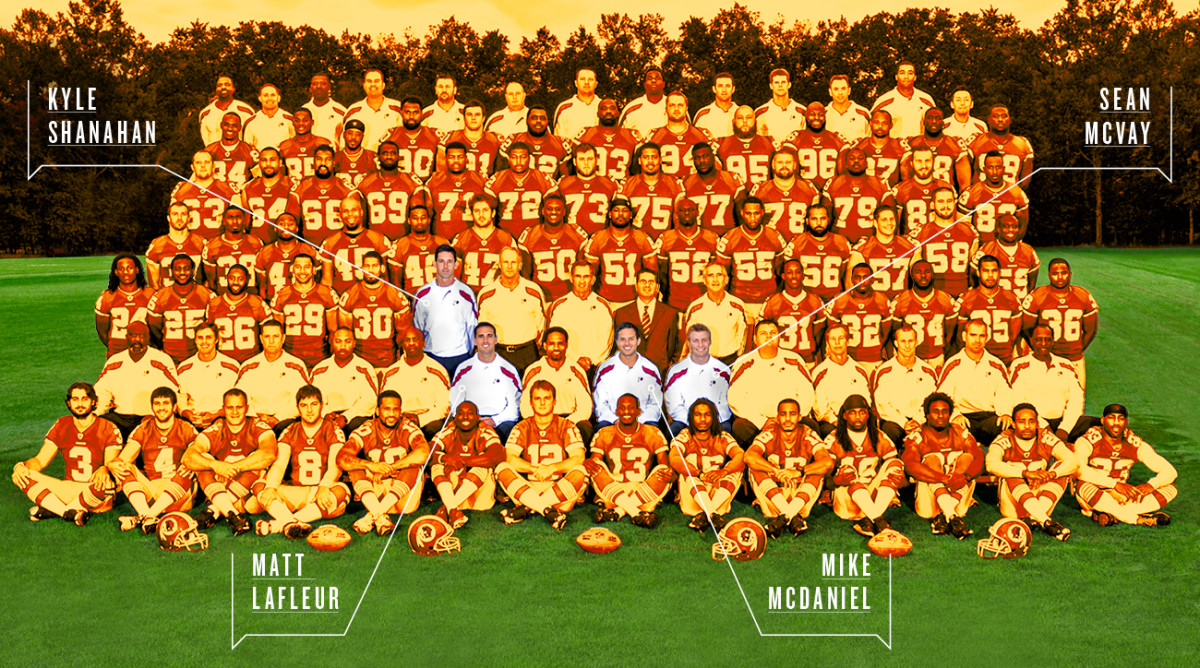

Six years ago, little was expected out of the men now filling the private back room of this upscale steakhouse in Thousand Oaks, Calif. Their four-year tenure at Redskins Park was defined by clashes with a meddling owner, issues with salary-cap management and little success. In four seasons under Shanahan, from 2010 to ’13, Washington lost 41 games, secured just one playoff berth and saw the rise and fall of a promising young quarterback. And yet, despite the middling record, internal discord and outdated facilities, buried in the deeply seated and oh-so public dysfunction, they created concepts that changed offensive football. Changes that grew out of so many nights much like this one.

They’re all here, at the dinner, for something called the QB Collective. It’s an organization dedicated to quarterback development, a program built around the principles to which they all subscribe. To Shanahan’s left are Matt LaFleur, the new Packers head coach, and first-year Broncos offensive coordinator Rich Scangarello; to his right, the 49ers’ co-offensive coordinators: Mike McDaniel (run game) and LaFleur’s younger brother Mike (pass). Absent this evening are two prominent members from that Redskins staff: Shanahan’s son, Kyle, the boss in San Francisco, and Sean McVay, the wunderkind Rams coach.

These men, once (derisively) labeled “The Fun Bunch,” either worked for Mike Shanahan in Redskins Park or apprenticed under someone who did. They can recite the quarterbacks who compiled their best seasons playing in some version of Shanahan’s timeless system. A partial list includes a Hall of Famer (John Elway), a league MVP (Matt Ryan), one of the most accurate passers in league history (Kirk Cousins), promising prospects (Jimmy Garoppolo, Jared Goff) and several journeymen who briefly shined (Brian Griese, Matt Schaub and Brian Hoyer). “It’s the best, most efficient offensive system in pro football,” Scangarello says. “It makes quarterbacks, not the other way around.”

The disciples consider Shanahan a misunderstood offensive genius, and they view that time in Washington not as the disaster the win-loss record suggests but as the start of something revolutionary. In a league where many franchises have been slow to innovate, and most coaches remain preoccupied with not getting fired, this group seems preternaturally inclined to take the opposite approach—which might be why they have amassed so many pink slips through the years. Although no one knew then, and few know even now, the concepts created and enhanced inside those coaching rooms—and restaurants and dive bars—have now spread across the NFL, and were utilized in two of the past three Super Bowls (by Kyle Shanahan’s Falcons and McVay’s Rams).

All the jokes this past spring about anyone in McVay’s orbit landing a head coaching interview missed the point. McVay is just one branch on a tree that took root not in Los Angeles, but in Ashburn, Va., for an organization that couldn’t see the genius.

Shanahan is 66. He hasn't coached football since Washington and can now be considered unofficially retired. He says it’s not for him to gauge how much credit that group deserves. Perhaps this is more telling: He says he will not write a book about his career and his philosophies. “Like with Silicon Valley,” he says. “You think they’re telling people what they’re doing?” The QB Collective has a competitive advantage it wants to keep.

The next day, Mike Shanahan leans back on a metal bench at Westlake High School. It’s a warm summer morning in Southern California, and dozens of top college quarterback prospects run through drills overseen by his adherents. Richmond Flowers III, a lesser-known member of that Redskins staff who has since left coaching and become an agent for coaches (he does not represent Shanahan), started the QB Collective as a way of sharing Shanahan's philosophies with lower levels of football. None of the men with whistles hanging around their necks believe they’re the only visionaries in pro football; this isn’t Al Gore taking credit for the Internet. But Shanahan is different, always has been, and that’s how he ended up in Redskins Park.

Explaining his philosophies, Shanahan starts with his influences. He studied and borrowed from high school or college coaches, who tend to innovate more than their pro counterparts; he took some tenets from Bill Walsh and others from Mike Holmgren, George Seifert and Alex Gibbs, the long-time offensive line coach considered the league’s premier zone-blocking guru; and, when he became the head coach in Denver in 1995, he applied everything he learned from nine previous stops. His offense became a product of all that, plus his intense analysis of the wishbone and the veer and Walsh’s famous West Coast offense, resulting in a scheme built on outside zone runs. “It kind of just happened,” he says.

Father and son spent all four seasons together in Washington.

Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty Images

Shanahan’s philosophy starts with the ground game—specifically those outside-zone runs. By sending most plays wide of the tackles, he sought to effectively cut the field in half—he could attack five to seven players more easily than all 11. He also wanted all his plays to look the same way at the start, whether it was an outside-zone run, a drop-back pass or a play-action bootleg. He ran several plays out the same formations, especially the three-man bunch (three receivers aligned close to each other) and the two-man stack (one receiver lined up directly behind another). He changed receiver splits—the distance the wideouts lined up from the tackles or tight ends—bringing them in tighter. That allowed them to block safeties on run plays and gave opponents a different look on passing plays. He would also change personnel within those formations. The limitless deviations meant he could change the scheme each week, targeting his opponent’s weaknesses.

Because Shanahan ran the outside zone, he needed faster, more athletic linemen, and because most teams weren’t looking for those types of players, he constructed dominating run games at discount prices. The Broncos won back-to-back Super Bowls in 1998 and ’99 with an offensive line featuring starters drafted in round seven (center Tom Nalen), round 10 (guards Mark Schlereth and Brian Habib) and not at all (tackle Tony Jones). After losing three previous Super Bowls, Elway accepted the run-heavy approach even as NFL offenses were throwing more, and running back Terrell Davis, a sixth-round pick, secured his bust in Canton during that dominant stretch.

What did all of this tell Shanahan? That his system worked. That great quarterbacks mattered, of course, but that efficiency at that position mattered more. He taught them like Walsh taught him, to read with their feet, to move in rhythm, spin through progressions, limit risk. If the golden-armed Elway could buy that philosophy, anybody could.

Shanahan also grounded his approach in an inventive spirit. As offensive coordinator in San Francisco, he once suggested to his head coach, Seifert, that the 49ers line Jerry Rice up in the backfield. Seifert blanched, at least until he saw linebackers trying to shadow the greatest receiver of all time. Shanahan would install plays that weren’t even in his playbook some weeks. He’d run 10 new variations out of the same bunch formation. Where offensive football in those days generally featured coaches listing what they could not do—can’t line up two tight ends, can’t split running backs into the slot—Shanahan helped usher in a new era. “The Can Generation” is what retired quarterback Trent Dilfer calls it.

Mike McDaniel grew up in Greeley, Colo., obsessing, like most kids in the Centennial State, over the Broncos. He became a Denver ballboy, then an undersized wideout at Yale. After graduation in 2005, when it came time to ask Shanahan for a letter of recommendation, the coach suggested he intern for the team, for free, instead. McDaniel was exactly the kind of intellectually curious young coach Shanahan wanted on his staff. He graduated from mindless tasks like helping repair the scout team jerseys to working for Kyle Shanahan as an offensive assistant in Houston for three seasons (2006-08).

A late-season collapse in 2008—and third straight non-playoff year—cost Mike Shanahan his job in Denver. He was out of the league for a year before the Redskins tabbed him to replace embattled coach Jim Zorn, who had been unable to develop Jason Campbell into a franchise QB. Shanahan would be Washington's new quarterback whisperer.

McDaniel joined him at Redskins Park in 2011. Once there, he found an environment unlike anything he ever could have expected, where ideas were not so much encouraged as expected, and to not evolve was tantamount to a fireable offense. “It was Steve Jobs—that aesthetic,” McDaniel says. “We weren’t outside the box; we didn’t have one.”

Mike Shanahan filled his staff with young, motivated coaches; most were early 30s or younger, many were in their first or second jobs. They were youthful enough to be fueled by ambition, close enough to boost each other, smart enough to apply what they were taught and competitive enough to turn everything—memorizing the most plays, sleeping the most nights under their desks—into a winnable game. Shanahan saw their relative inexperience as a strength, and he fostered their youthful exuberance. “Just a bunch of overambitious, average athletes,” McDaniel says. “We’re all Napoleon Complex dudes. And we’re competing against people that are the exact opposite dichotomy—they’re all, What are the rules? What did Bill [Belichick] say to do?”

Flowers grew up in a football family—his father played for the Cowboys and Giants. But he knew right away that his co-workers were different. “I tried for so long to convince myself that maybe if I studied harder or watched more film, I’d start loving it the way that those guys do,” he says. “It became clear to me that I was never going to out-guru them. It was the most humbling four years of my life.”

Shanahan saw the future in the unlined faces that stared back at him. That started with Kyle, the prodigal son. For years, he had implored his father to join forces, but dad had laid out three non-negotiable conditions: 1) Kyle had to become the offensive coordinator for another team; 2) He had to call the plays for that offense; and 3) That offense had to finish the season in the top five in total offense. Otherwise, he told his son, “They’d call that nepotism.” Kyle met all three prerequisites in only his second year as a play caller (with Houston, the league’s fourth-ranked offense in 2009). He was 30 when his father hired him as the Redskins’ offensive coordinator.

Mike placed Kyle in charge of modernizing their scheme. “There’s no doubt that Kyle has the best offensive mind of anyone I’ve ever been around,” says Scangarello, who wasn’t in Washington but worked for Kyle at two other stops.

Matt LaFleur, then 30, came with Kyle from Houston to become the Redskins’ quarterback coach. He was more thorough, detailed and exacting than any of the assistants, able to find mistakes on even the most explosive plays. Early in his tenure, he heard a someone yelling through the wall next door as he scribbled on a whiteboard. “Who’s that?” he wondered.

As it turned out, Mike Shanahan was conducting an interview for an offensive assistant opening. He knew the applicant’s grandfather, John McVay, a former Niners GM who with Walsh had constructed one of the NFL’s great dynasties. After meeting with 24-year-old Sean, who had grown a beard to look older, Shanahan canceled three other interviews.

Shanahan tasked McVay with binding playbooks, making copies, scribbling out play sheets and organizing cutups of opposing defenses. In his spare time, McVay drew X’s and O’s on the white boards in the meeting rooms—obsessed with writing each letter with impeccable penmanship. He could study another coach’s play sheet for 20 minutes and recite more than 100 plays. He even remembered random sequences from meaningless games played by other teams, just from casually watching them on TV. “It’s almost like remembering a song for him,” McDaniel says. “He’ll narrate a game situation in his head and remember it forever.”

Offensive line coach Chris Foerster, who at 48 was one of the coaches on the staff with actual experience, remembers introducing himself to McVay and LaFleur—“two fuzzy-faced kids”—on his first day at Redskins Park. He assumed the duo performed menial tasks like picking up players at the airport. In reality, their ideas—many honed with salt and pepper shakers during happy hour at watering holes like the Ashburn Pub—were making their way into the playbook.

In 2013, CBS Sports ran a piece labeling Kyle Shanahan difficult to work with and over-empowered to shape the offense. The story tabbed his assistants, all the young coaches other than McVay, as sycophants, yes men, there to appease the Shanahans, having not earned their coaching stripes.

They were young. They knew that. But that gave them perspectives football lifers lacked, the license to be creative. “Almost like, Can you believe this?” Flowers says. “Here was a multi-billion dollar organization being run by a bunch of 25-year-olds.”

The Redskins went 6–10 in 2010 and 5–11 the next year, due to a lethal combination of a lack of talent, no cash flow to rebuild and injuries. Finding a quarterback remained an issue. They had gone with an aging Donovan McNabb and a rehashed Rex Grossman. They tried out John Beck, a 2007 second-round pick of the Dolphins they publicly touted. Privately, they knew better.

As the 2012 draft approached, the coaches scoured the QB class. They traded three first-round picks and a second rounder to move up and take Robert Griffin III—the preferred choice of owner Dan Snyder—second overall. In typical Skins fashion, they took Kirk Cousins—favored by coaching staff—three rounds later, setting themselves up for a future QB controversy.

The Griffin selection forced the coaches to innovate like never before. It quickly became apparent that for all his skills—arm strength, athleticism, speed—Griffin couldn’t read a defense. So Kyle set out to make another alteration, stitching in a familiar concept: the zone read.

The staff gathered in the film room one memorable spring afternoon—his assistants joke that Mike locked them inside. They ran through cut-ups of Tim Tebow’s time in Denver, Cam Newton’s rookie season in Carolina and Griffin’s career at Baylor. “We watched the same film, I swear, 50 times,” says Foerster. When they finally finished that session, Mike told them, “Let’s run it back again.” To which Kyle, exasperated, replied, “Dad!?!?”

From those sessions came a simplified scheme designed to capitalize on Griffin’s strengths. The Redskins mixed outside zone runs with a heavy emphasis on zone reads and far more play-action than normal, putting their quarterback away from center but not deep in the shotgun—the Pistol formation.

The good times rolled during RG3's rookie year, for the quarterback and the offensive cooridnator, Kyle Shanahan (in white).

Jonathan Newton / The Washington Post/Getty Images

Despite starting 3–6, Washington rattled off seven straight wins. The ground game dominated—just like in Denver, it was built around a sixth-round running back and an unheralded front five. Alfred Morris ran for 1,613 yards, a tally he would never again approach. The Redskins, as a team, gained 2,709 yards on the ground to lead the NFL. One concept, a five-step drop where Griffin faked a handoff, turned his back to the defense, planted his feet and threw quick, safe attempts, produced more than 1,000 passing yards alone. He won Offensive Rookie of the Year and made the Pro Bowl.

“You don’t understand,” Flowers, then an offensive assistant, remembers telling his wife, “we’re doing something right now that is monumental, creating almost a brand-new offense, something the NFL has never really seen.”

The Redskins finished 28th in total defense and trotted out one of the worst special teams units in the league. They still made the playoffs. Against the Seahawks in the wild-card round, they started a hobbled Griffin, who had injured his right knee four weeks earlier. In the fourth quarter, he blew it out.

Even after recovering from the knee injury, Griffin would never again approach the success of that season. Neither would Shanahan and his Fun Bunch, at least not right away. After a 3–13 campaign marked by an inability to expand the passing offense with Griffin under center, a too-late switch to Cousins and an eight-game losing streak to finish out the year, they were let go.

Among the offensive coaches, only McVay stayed in Washington to work under Jay Gruden, the coach hired as Shanahan's replacement. The rest of the staff spread out, with branches of the tree sprouting in Cleveland, Atlanta, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Green Bay, Cincinnati and Denver.

Kyle took McDaniel with him to Cleveland in 2014 and hired Mike LaFleur as an offensive assistant. They ditched the zone read elements from Washington and reconstructed the system to maximize Hoyer’s skills. After a 7–9 season—the only year during the 10-year span from 2008 to ’17 that Cleveland avoided double-digit losses—they left, Shanahan bristling at the front office's insistence on playing Johnny Manziel. According to McDaniel, bouncing around actually made them better. “When you’re getting fired but still in the league, you get jobs where you gotta figure out how to make s--- work,” he says. “That made us a thousand times better.”

From Cleveland the crew moved on to Atlanta, where they inherited an established quarterback in Matt Ryan and tasked him with throwing on the move, re-inventing once again. In their second season he won NFL MVP honors as the Falcons made the Super Bowl. “You could sense the brainpower in that room,” Ryan says. “That pushed all of us in ways we hadn’t been pushed before.”

Left to right: McVay and Kyle Shanahan have established themselves as head coaches in the NFC West, while Matt LaFleur is the new guy in Green Bay and McDaniel serves as one of Shanahan's co-offensive coordinators.

Getty Images (4)

McVay left the Redskins for L.A. in ’17, becoming the youngest head coach in NFL history. He hired Matt LaFleur away from Kyle Shanahan and the Falcons, and together they designed their own version of the offense. They deployed play-action heavily, fueling Goff's breakout year. One of his assistants, Zac Taylor, was hired as the Bengals’ new head coach last winter.

Kyle Shanahan, Mike LaFleur and McDaniel went to San Francisco in ’17 and, out of necessity, designed an offense around two tight ends. This season, they collected shifty and speedy running backs, intending to deploy big-play threats out of the backfield—playmakers at an affordable price. Matt LaFleur, after spending last season as the offensive coordinator in Tennessee, is now the head coach in Green Bay. When Ryan ran into Aaron Rodgers at a golf tournament, the Packers’ QB asked about the system. “You’ll love it,” Ryan told him.

As for Mike Shanahan, his legacy is complicated. “I know the wins and losses weren’t what they wanted in Washington,” Mike LaFleur says. “But I don’t believe that [stretch] defined his legacy. He’s one of the top innovators in pro football, ever.” The six quarterbacks who played at least two seasons under the Godfather all made at least one Pro Bowl. No other coach in NFL history can make that claim. “Matt Ryan, if he never met us, might [still] be a Hall of Famer,” McDaniel says. “It isn’t like, Oh, we s--- out genius. But he was proof of what before was abstract theory: The system makes a tangible difference.”

Back at the QB Collective camp, the coaches patrol the field, correcting prospects on their footwork, fine-tuning their releases. McVay tells the quarterbacks stories of Navy SEAL training techniques. Matt LaFleur wheels around on a scooter, a cast on his right leg after he tore his Achilles playing basketball last spring. Drones buzz overhead.

If the coaches closed their eyes, they might be transported back to Redskins Park, to the fresh faces and The Fun Bunch, when they innovated because they were forced to, because they didn’t know better. And they eventually succeeded, changing offensive football, perhaps because they had a chance to fail.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.